I’ve taken some time at the end of December to look back on the previous year and think about what I want for the coming year.

In 2024, I wanted to build upon the success of 2023, a year that saw me hitting a sales goal for the first time.

One sale per month is barely pizza money, but it is a start, especially since I had never earned that many sales before in the years I’ve been trying to run my indie game development business.

However, I decided that metrics like the number of sales isn’t really an actionable goal. It is more of a lagging metric.

So for 2024, I have the following outcomes I am aiming for:

Increase my newsletter audience from 30 to at least 42 subscribers by December 31st

Earn at least 2 sales per month by December 31st

As for actionable goals:

Release at least 2 Freshly Squeezed Entertainment games by December 31st

Perform at least 2 SEO activities per month by December 31st

My thoughts were that if I make and publish games AND do things to make my website more effective and easier for people to find what they want, then I can increase my audience and my sales.

So, how did I do?

My Goals

Published Freshly Squeezed Entertainment Games (Target: 2) — 0

Two games a year for someone to work on alone very, very part-time is technically doable, but I haven’t been able to do it yet.

In fact, I didn’t do it last year, either:

That’s two years in a row in which I did not publish a new game.

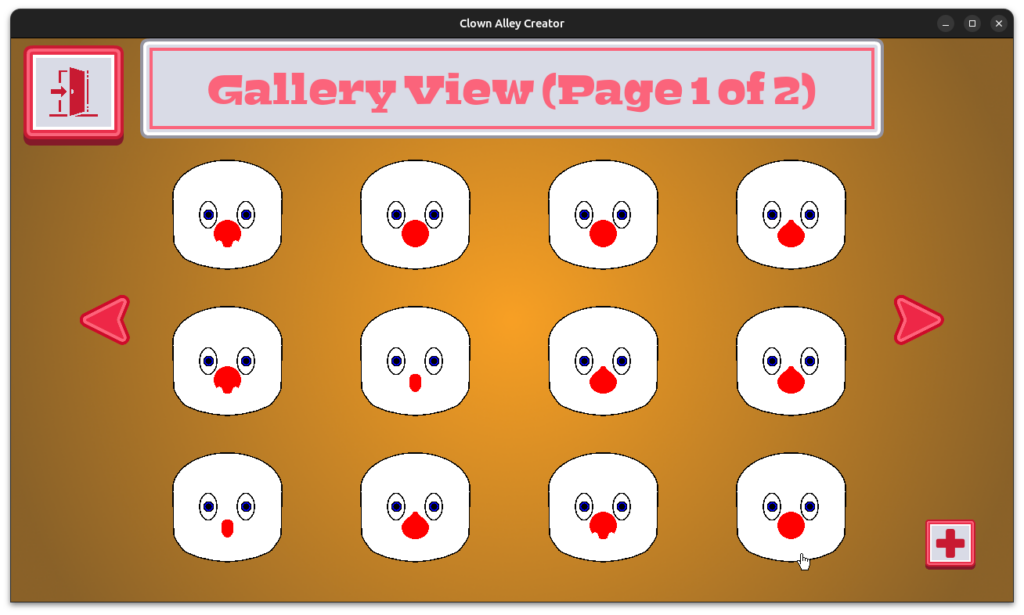

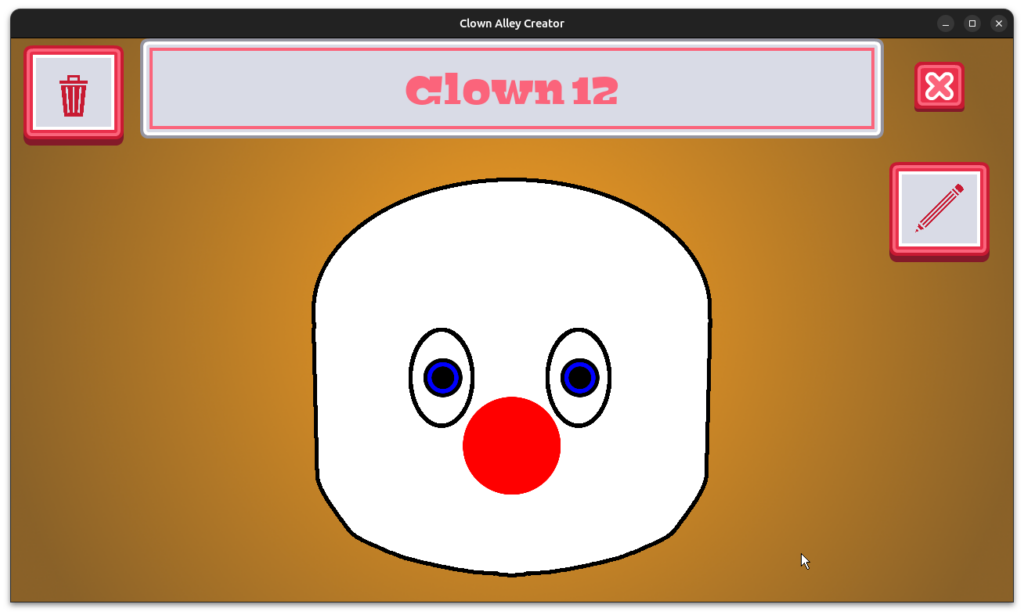

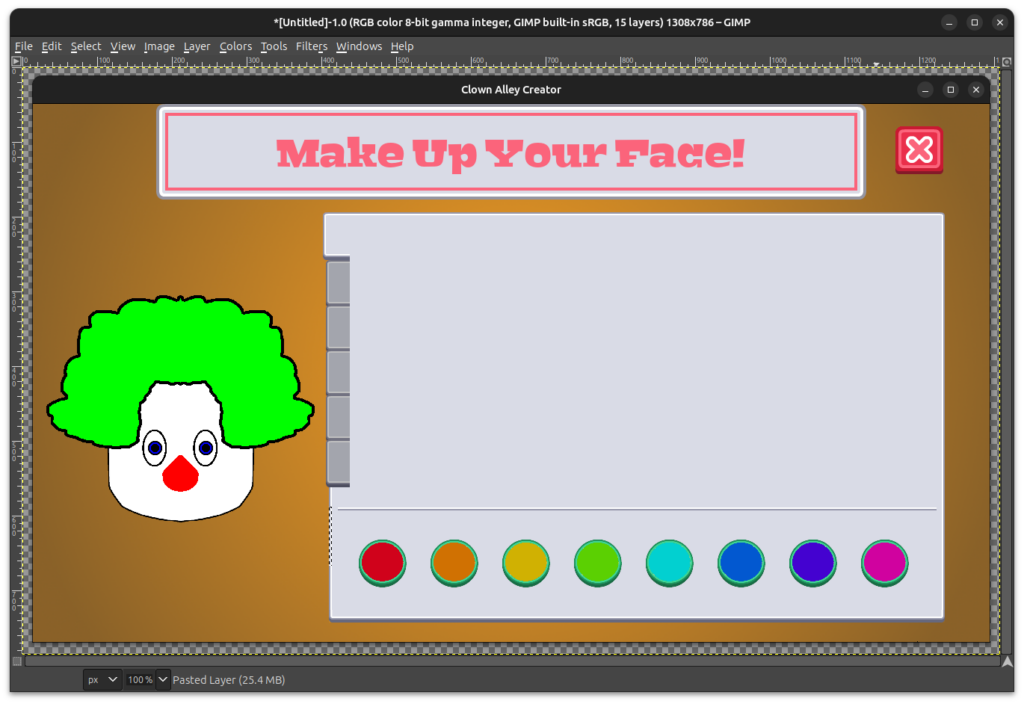

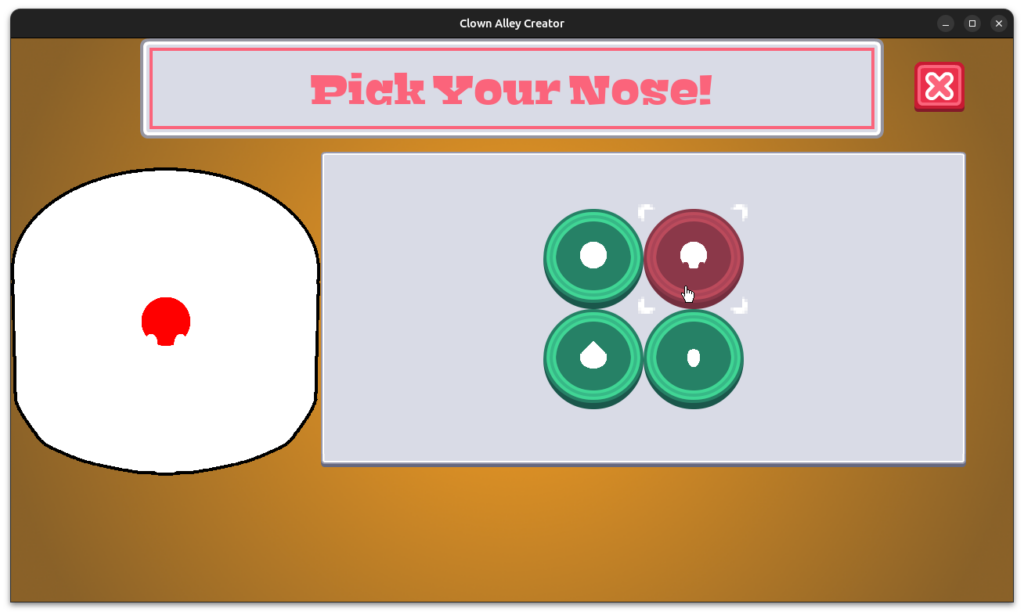

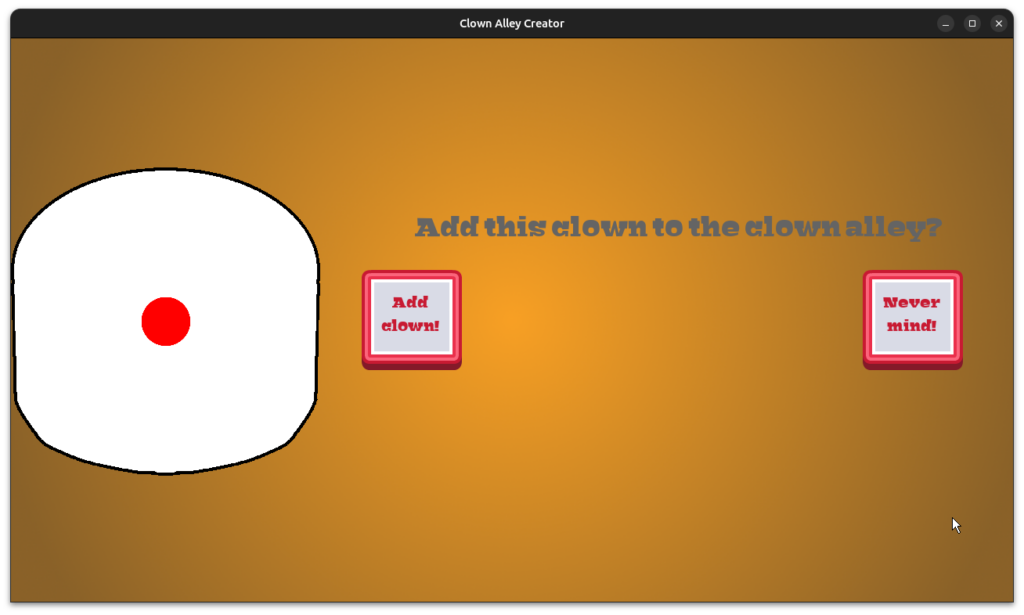

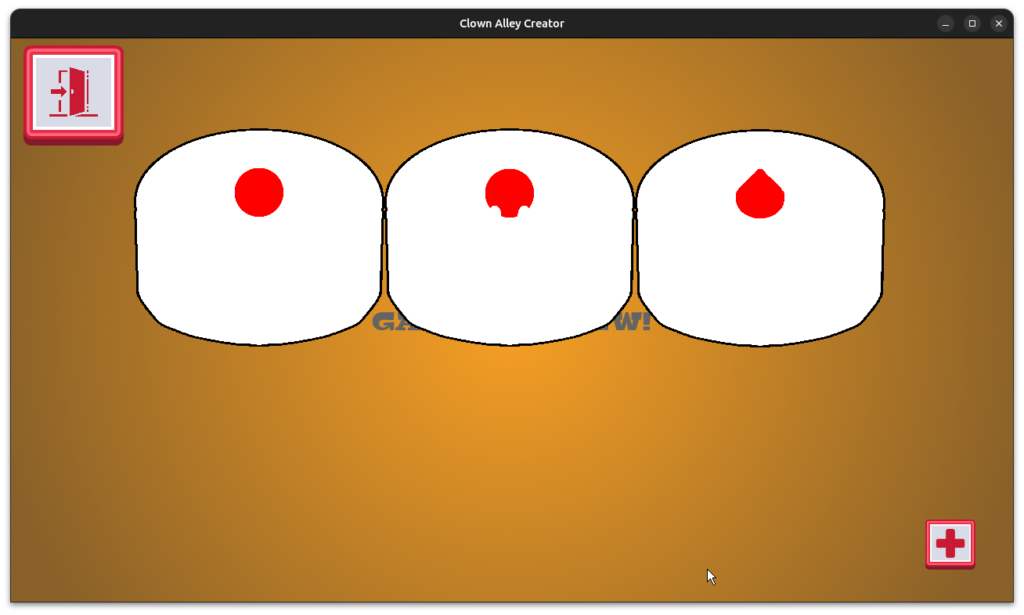

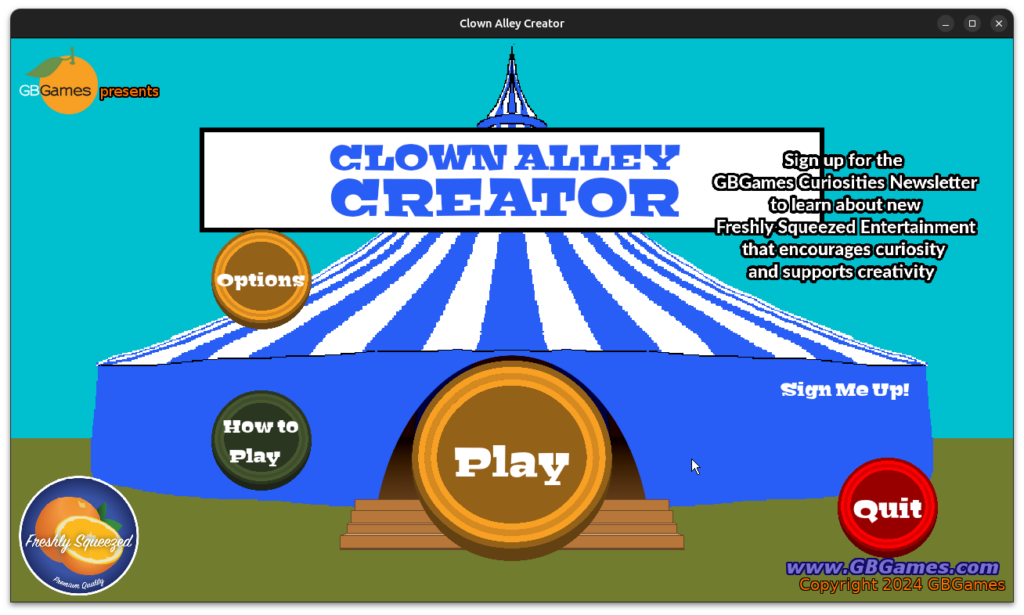

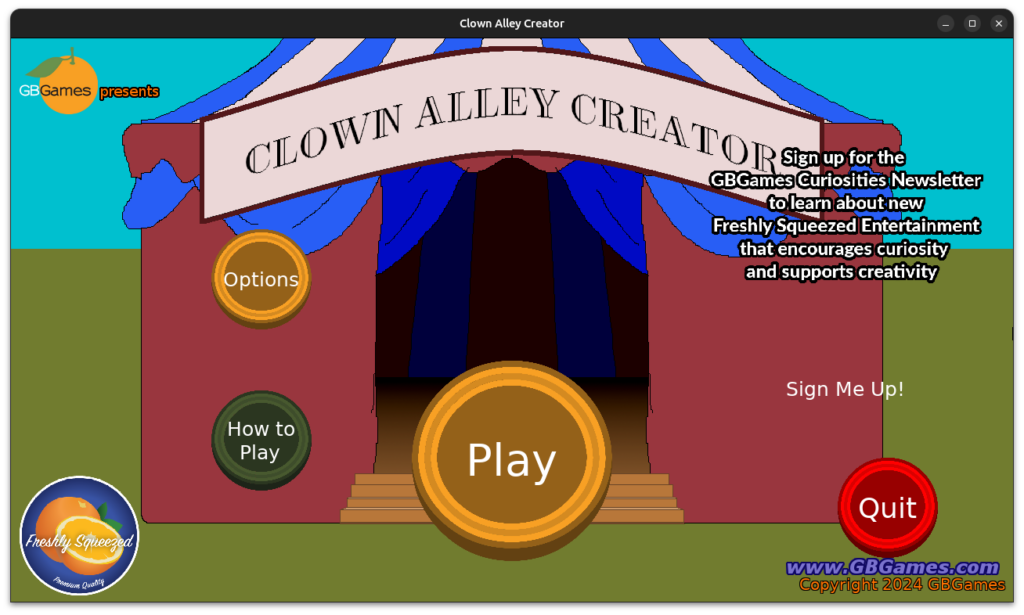

Much of my current business strategy depends on releasing games in my Freshly Squeezed Entertainment line, which are polished, playable prototypes that provide complete entertainment experiences and are given away for free. The general idea is that the games are supposed to be quick to develop and have a low barrier to entry so that they are more likely to find an audience. I hope to get feedback from that audience, and if enough interest exists, I can always create a “deluxe” version of the game that I can sell.

So not releasing a game isn’t great, because there cannot be an audience for a game that doesn’t exist.

At the end of 2023, I had put in a year of game development effort into a family-friendly, non-violent party-based role-playing game called The Dungeon Under My House, and it wasn’t anywhere near done yet. I didn’t have any reason to be optimistic that I could complete it within six months of 2024, but I moved forward as if I could.

About 20 months into the six month project, I decided to put it on hold. I finally sat down and scoped out what I thought the rest of the project looked like, and an optimistic estimate said I still had at least another year of development. Oof.

So I made the hard decision to put the project on hold. I published a post-mortem for The Dungeon Under My House, and I hope one day to publish a second one after I return to the project and truly finish it.

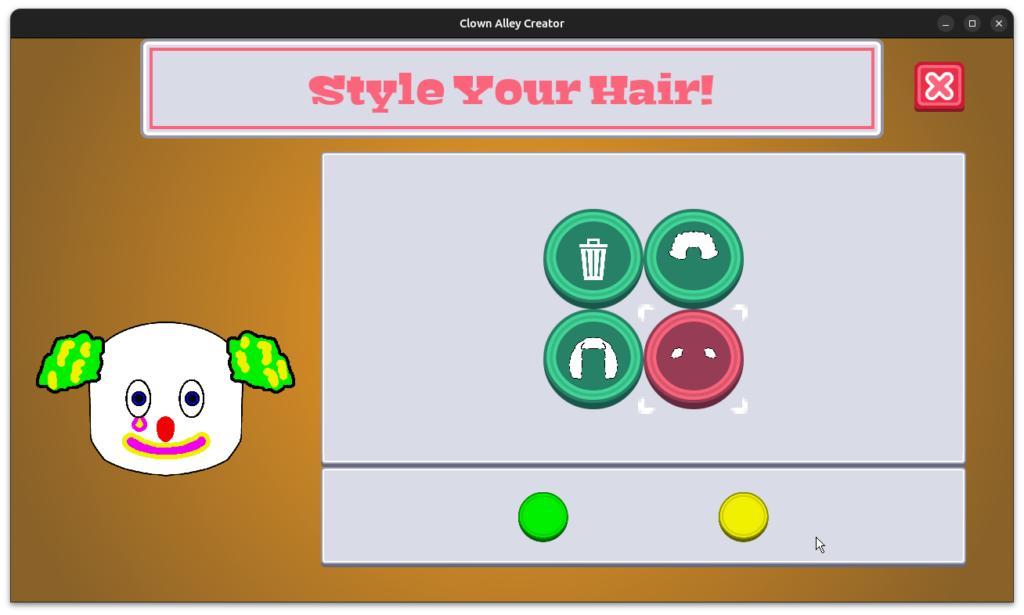

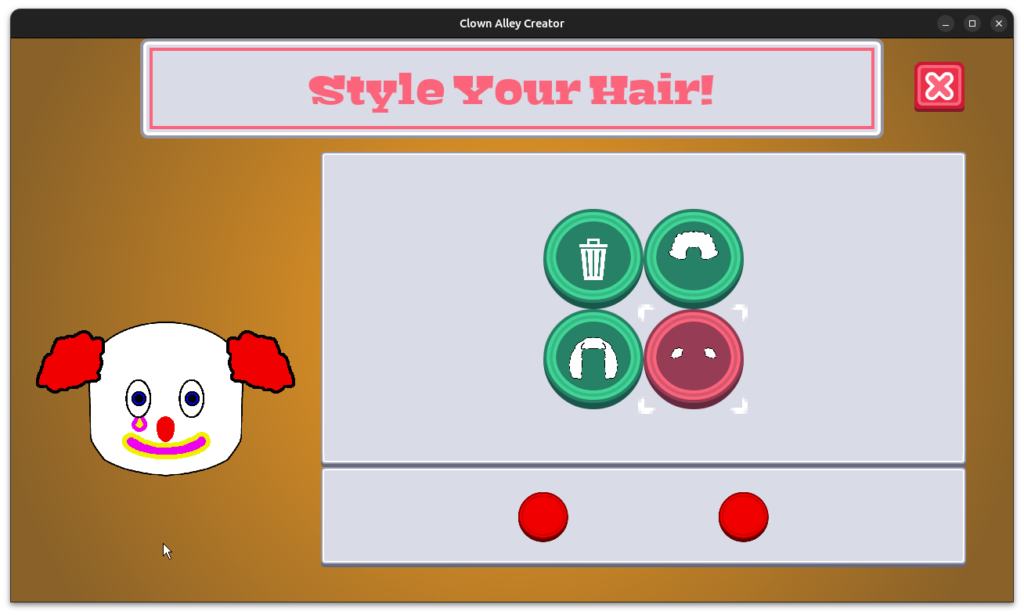

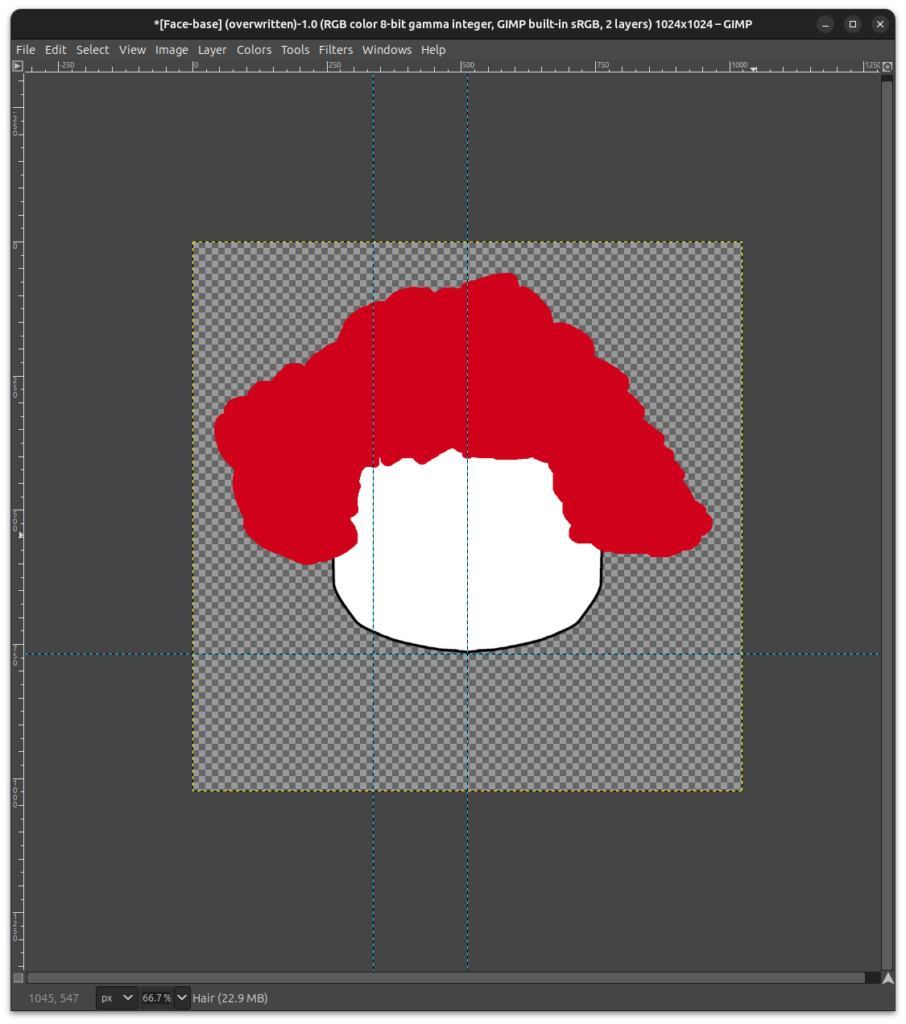

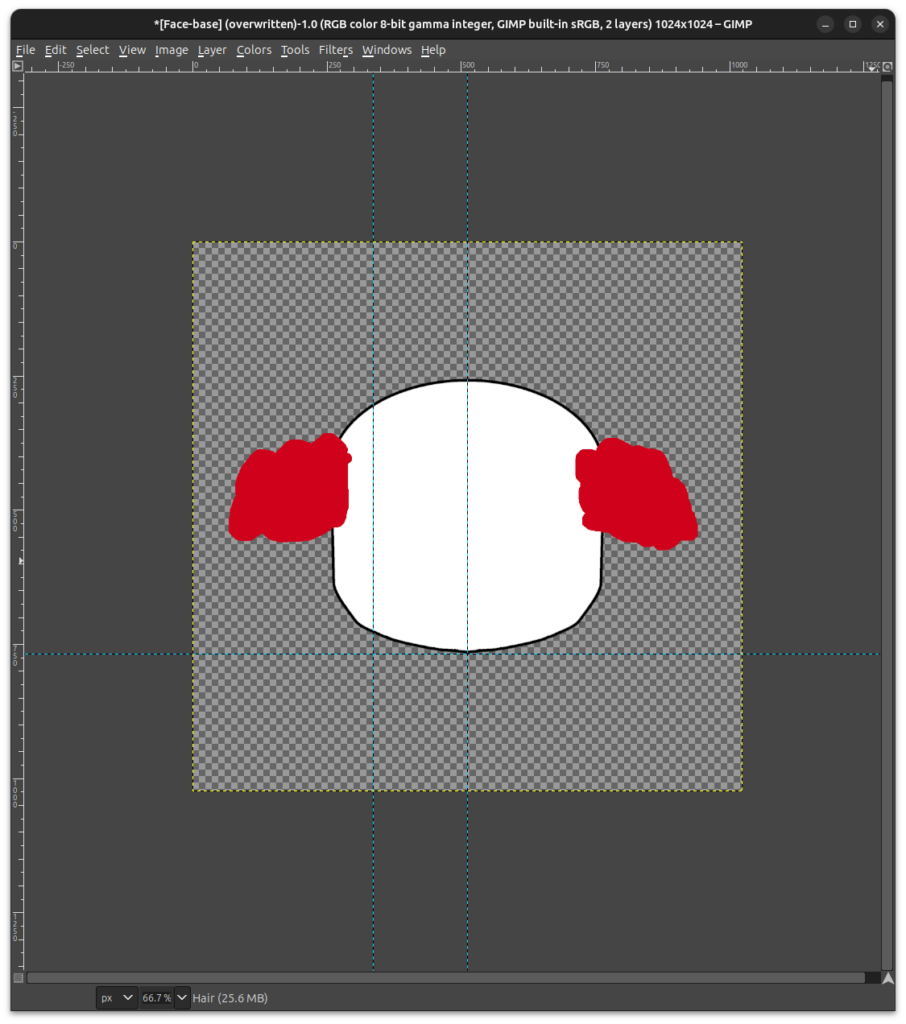

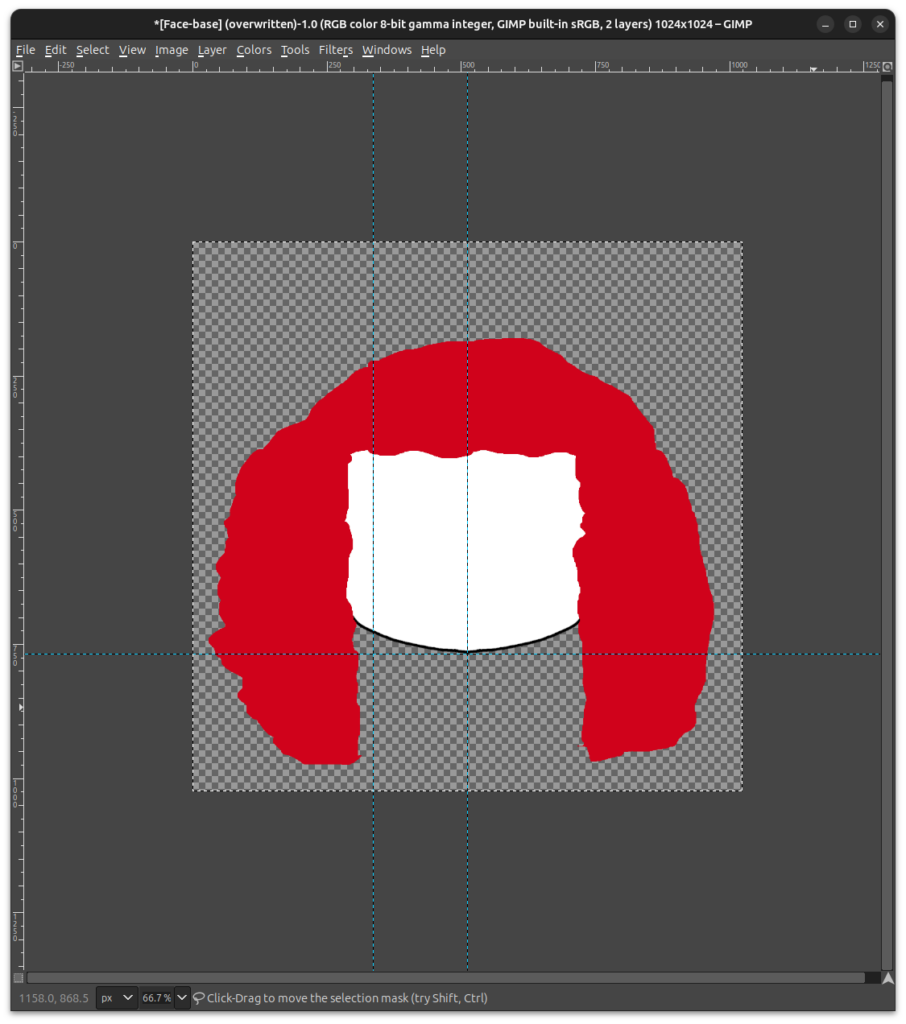

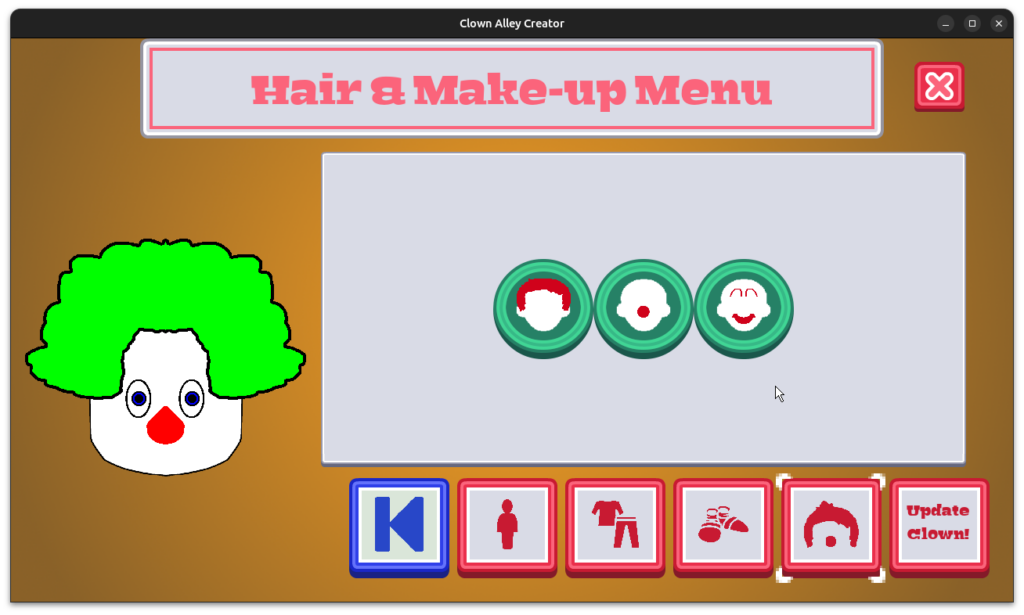

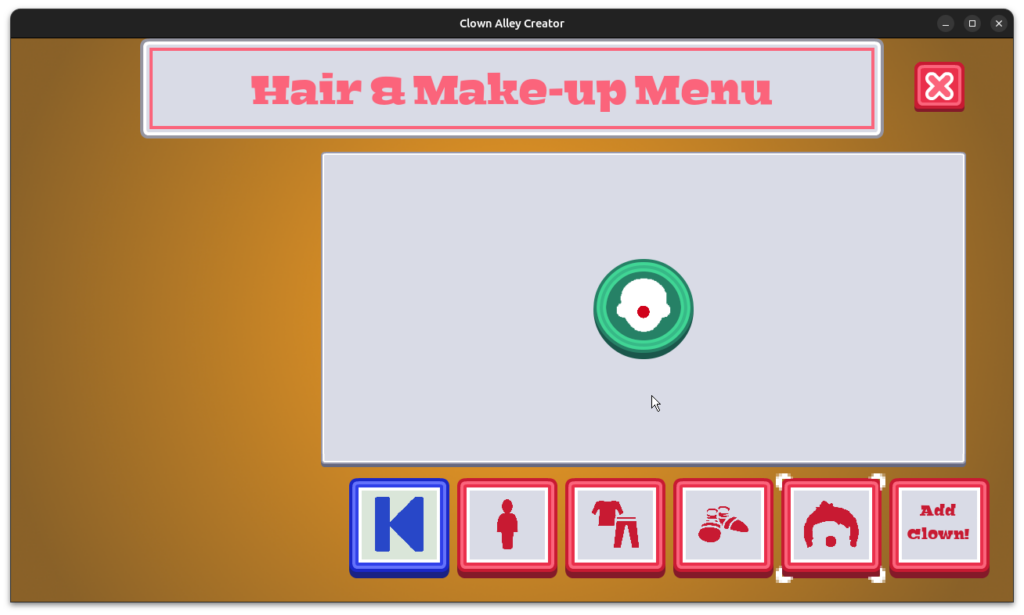

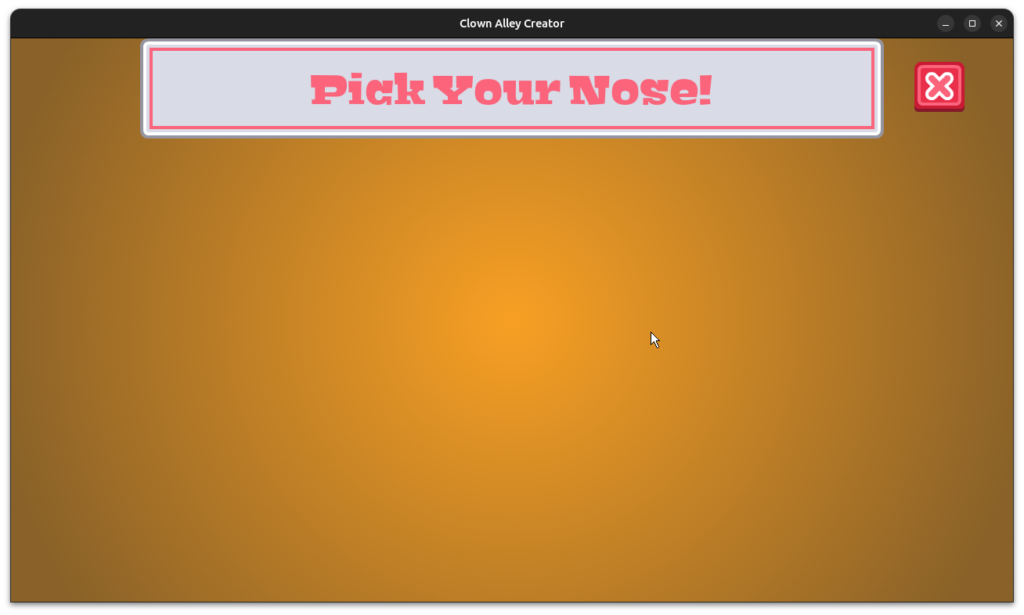

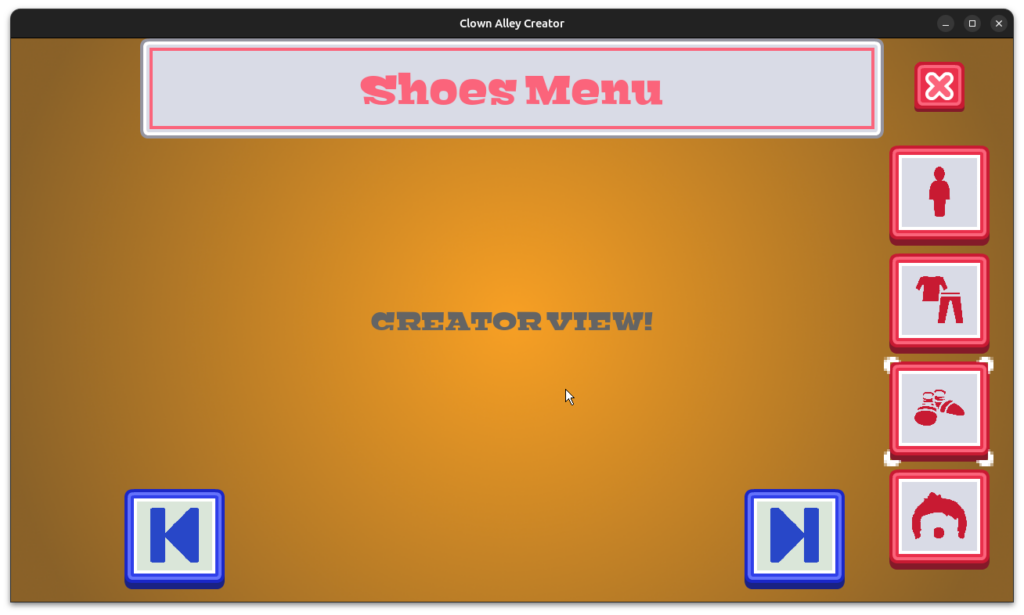

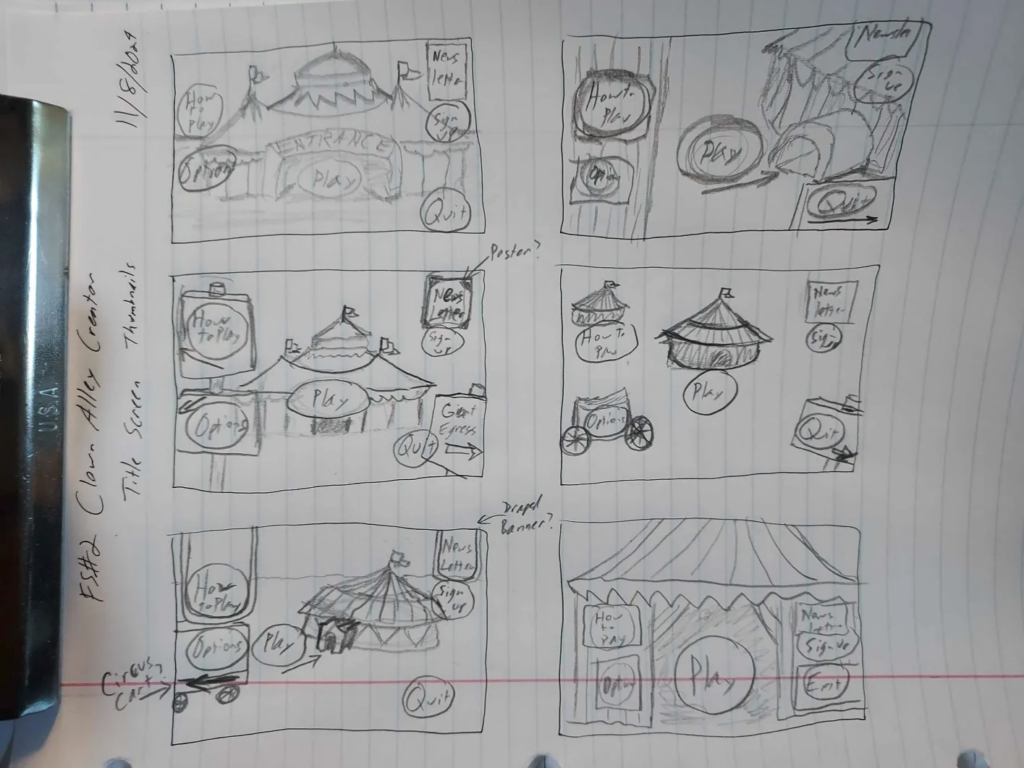

For now, I started work on a project with a much smaller scope. I normally try not to plan everything upfront and instead let the project build up in iterations.

This approach works fine. I’ve built and published games this way. But it clashed with my goal of releasing games quickly. I had to recognize that there was a difference between publishing a game eventually and publishing a game on a more or less predictable schedule, and that only the latter was going to help me satisfy my business goals.

Thanks to some advice I got from Dora Breckinridge (you should hire Dora, by the way), I decided to try to truly capture as much of the scope of my new project as I could, plan on working on features and technical infrastructure for only part of the project’s schedule, and leave the lion’s share of the schedule for leveraging what I had built to fill in the content of the game.

As of this writing, I am finishing up the first phase of work, and thanks to a realization I had about how to arrange the work in a more Agile way, I am incredibly confident that I will ship this project in six months easily, mainly because the project will always be in a shippable state long before then.

Basically, I went from a project with no end in sight to a project that could potentially be done early if I really want it to be.

However, it won’t be released in 2024. I can’t work miracles.

Perform at least 2 SEO activities per month by December 31st (Target: 24) – 2

Ok, so I abandoned this one fairly quickly. SEO felt like a solution that might not make sense in a world where search engines are getting less useful and almost actively hostile towards websites that aren’t in the top results, plus a world where genAI is allowing people to churn out garbage so cheaply that the search results are polluted anyway.

Also, my website barely gets any traffic. Not like it used to when I had more time to blog more frequently about a variety of topics, anyway. Much of that existing traffic is from game developers interested in my blog posts about project management and copyright for indies, and so not necessarily people who would be in the target audience for my games.

But just having this goal, even if I did give up on it, did get me to make some important changes.

I felt like I didn’t have a good baseline to know if my SEO was actually doing anything positive. I didn’t want to make a bunch of changes without any concern about how effective they were. A change could produce a negative outcome, and I would want to revert that change right away. But how would I know?

So I started creating automated metrics reports from my website, plus I started grabbing page visit and download data from the various app stores my games are in and throwing them in a combined spreadsheet. It’s a bit more manual of an effort, but it is worth it to know this data, and I can probably figure out how to automate some of it.

These metrics came in handy when I decided to experiment with ads for part of the year, giving me a good insight into whether or not a particular ad was moving the needle for my games in any particular app store.

I think I might revisit this goal for 2025, not because I want to improve my search engine rankings but because there are things I could do to make my website look and feel better to people who actually visit it. If I optimize the site for real people and their goals as opposed to trying to appease some search engine algorithm, I think things will work out better for everyone.

My Outcomes

GBGames Curiosities Newsletter subscribers net increase (Target: 12) — net 4

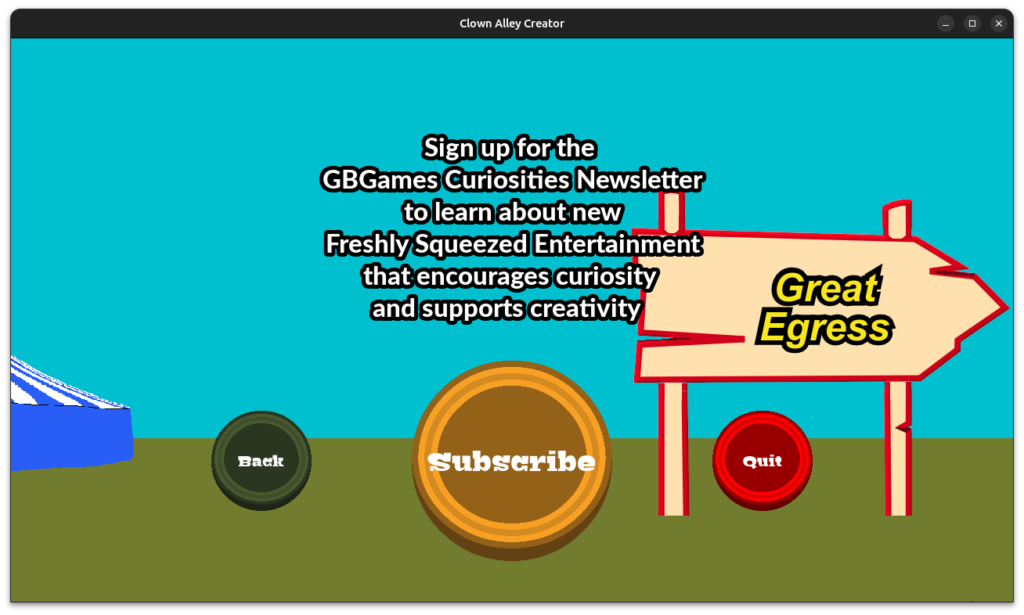

My current business strategy has my GBGames Curiosities Newsletter at its core. I want to cultivate an audience of people who specifically said that they wanted to hear from me and are fans of the kinds of games I make.

I don’t have many subscribers yet, and this is the second year in a row in which I was aiming for a net increase of one subscriber per month and didn’t make it.

Unfortunately, I didn’t do anything specifically to try to grow the list, so any efforts to do so were one-offs and not consistent at all. Still, I gained 4 subscribers and lost 0, which is a positive trajectory.

Clearly if I want this number to be higher, something needs to change in terms of my approach.

Earn at least 2 sales per month by December 31st (Target: 24) – 16

Last year I sold 13 copies of my games, beating my 1 sale per month goal by one. I was sure that doubling the goal was both ambitious and doable, especially if I kept up my promotion efforts.

Unfortunately I did not, as I spent much of my capacity trying to make progress on game development.

Now you might think that at least 16 sales is more than 13 sales. And it is true.

But the reason most of those sales appeared is because I spent money on Facebook ads, and unfortunately I spent more on ads than I earned in sales income.

On top of that, this is the first year I have put my game Toytles: Leaf Raking on sale. I was experimenting with the price to see if it might encourage more purchases at a lower price point, or if the act of being on sale made it show up more easily in various app stores. In the end, I think it just served to earn me less money for each sale.

To compare, in 2023 I sold 13 copies of my games and made a total of $103, much of it because of people contributing more than the minimum amount on itch.io. Despite selling 16 copies of my games in 2024, I only made $76 from those sales, and 0 came from itch.io.

Analysis

I sold more copies of my games but made less money, as I said above.

I didn’t take advantage of itch.io sales as much as I maybe should have. I think I was disappointed in the amount of work I put into some sales at the end of the previous year that resulted in nothing, and I am also wondering why I don’t always get advance notice from itch.io about joining an upcoming sale so I can prepare.

But frankly, most of my effort went into game development and not promotion, and so it is no wonder I didn’t see more success in terms of sales.

Last year, I said that my megaphone is tiny, and it still is.

My website has very little organic traffic, and my social media accounts all have limited ability to get awareness out.

I said then:

Basically, the more I rely on social media to promote my game, the more effort and/or money I need to expend for at best a temporary boost in potential traffic.

Focusing on social media isn’t sustainable, and it is partly why I wanted to focus on SEO. However, I worry that the days of useful search engines and a useful Internet in general are behind us.

So should I focus on advertising some more? Maybe. In my experiments this year, I basically proved to myself that if I could get my game in front of the right people that some of those people do, in fact, purchase the game.

That’s good!

But ads are too expensive to run for one-time sales, and I don’t have enough of a backlog of games to cross-sell and make it worth it.

However, if I focused on promoting my mailing list rather than any one particular game, then perhaps the calculus changes significantly. One purchase of a game today doesn’t necessarily mean more purchases in the future, but one mailing list signup today means being able to promote my games indefinitely.

On the other hand, it is entirely possible that people are finding that their inboxes are getting more and more useless the same way that search engines and the Internet as a whole are getting worse. Maybe all the data about how mailing lists are still very effective isn’t accurate anymore?

Or maybe they are, but most game developers are so tied to the app stores and Steam that they don’t find mailing lists useful for THEIR business models.

And I think my target audience doesn’t necessarily even know what Steam is, let alone uses it for finding and playing games.

Relying on Apple and Google to sell my games is therefore a bit risky because I have no way to contact the players who play my games unless they specifically sign up for my mailing list.

Some numbers

I did a total of 359 hours of game development for the year.

For comparison, a full-time game developer working 40-hour weeks would have accomplished that number in a little over 2 months.

I did 62 hours of writing and published 59 blog posts and 12 newsletters.

I did 23.75 hours of video development and published 12 videos.

The above mostly represents a weekly development log, plus the occasional video update, as well as some one-off blog posts and sale announcements.

I originally continued the weekly devlog videos, but the amount of work that went into each video took away from development work. After a couple of months of this pace, I decided to release videos once a month or so. It meant more details in each video, making them more compelling for viewers, plus an easier work schedule for me.

I wanted to focus on my health. In 2022 I had horrible back pain due to an unknown reason, and I think my regular morning exercises are keeping me strong enough to keep it at bay, but I felt like missing a day of exercises was enough to make day to day living feel risky.

So I started doing more exercises meant to help build up strength and stability. I used to do yoga, but I think I was doing something to cause problems. Instead, I started doing weight/resistance exercises.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t keep things up. My knees were hurting until I stopped doing squats only a couple of months after I started doing them, which is too bad because they were supposed to be a great all-around exercise. I did 780 squats total.

Also, my wrists were bothering me from doing push-ups. I stopped doing them in May, so I ended the year with only 1,230 push-ups.

The good news is that I added regular walking, slowly building up from 10 minutes a day to 25 minutes a day and from 2 mph to now warming up at 2.4 mph and increasing to 3.2 mph before cooling down at 2.4 mph again. I have done about 50 hours of walking for the year.

As for losing weight, I didn’t want to count calories or anything too onerous, so I simply cut snacks. I now eat three meals a day and if I have a snack it is once in awhile. I probably still have dessert too often. But I ended the year down a few pounds, despite heading into the holidays to potentially gain them all back.

I read a total of 60 books, of which 26 were audiobooks. Some favorites include:

- Creativity Inc by Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace

- The Impact of Iwata by Lucas M. Thomas

- Secret Iowa by Megan Bannister

- Black AF History by Michael Harriot

- What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (first time reading it since it was assigned reading in high school)

- Useful Delusions by Shankar Vedantam

- Killing Commandatore by Haruki Murakami

- Hunter by Val Gale

- Natural Beauty by Ling Ling Huang

- Procedural Generation in Game Design by Tanya X. Short and Tarn Adams

- Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

- LAN Party by Merritt K

- Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Zero by Charles Seife

- Finna by Nino Cipri

- This Is What It Sounds Like by Susan Rogers and Ogi Ogas

- To Sleep in a Sea of Stars by Christopher Paolini

- Mindful Games by Susan Kaiser Greenland

I was playing Minecraft heavily in the beginning of the year. I played in Hardcore mode, but each time I died, I would create a new world with the same seed and play again. It was like Groundhog Day in that I can’t keep anything I made except the memory of where resources and landmarks were located, and I found it quite compelling.

But otherwise I wasn’t playing games regularly. Steam says I only played 3 games, but most of the games I do play tend to be through GOG or Humble or itch so that’s not representative.

I found out that Flatspace, a game I reviewed a long time ago for GameTunnel.com, is available on Steam, so I played that game quite a bit. I played a little Tooth and Tail as well as Gods Will Be Watching. None are recent games.

More recent games included Once Upon a Jester, which I really enjoyed.

But the game I probably played even more was Kitsune Tails, a fun Super Mario Bros 3-inspired platformer, which did release in 2024, so I’m still hip and with it.

Goals for 2025

Once again, my goals will focus on game development efforts and promotion efforts.

I ended the year feeling very positive about being able to ship my next game in a few months, and I think it has given me confidence that I can repeat this feat.

But I also want to revisit Toytles: Leaf Raking, partly to improve it, which I know will take up some time. While I’m proud of the game and think it is still a good one, I can tell that it is rough around the edges and might not appeal to more people because of it, especially from screenshots.

So two actionable goals are:

- Publish at least 1 free game by June 30th

- Publish major Toytles:Leaf Raking quality improvement update (including demo) by December 31st

I think I’ll easily accomplish the first one early. I already have almost two of months of effort in, so I should be able to finish this six month project by the end of April. Still, I’m one person and very, very part-time at that. I could get sick, my day job could take up more of my time, or there might be family emergencies. So between April and June, expect my next Freshly Squeezed Entertainment game.

Meanwhile, I clearly need to do something more proactive and consistent in terms of getting my games in front of people.

I don’t know if I can capture it in a goal by quantifying specific activities such as SEO or ad campaigns, though.

In fact, those are tactics, and while they might be useful and important, I find that I struggle because I don’t have an overarching strategy for them to fit into. I’ve put the cart before the horse.

There are some fundamentals to marketing and selling a particular game, but I also want to promote GBGames as a whole.

Specifically, I want more people to think of GBGames when they think of compelling entertainment that encourages curiosity and supports creativity. I want people to think of GBGames when they think about family-friendly, LGBTQ+-affirming entertainment. I want people to think of GBGames when they want to play games that respect their time and their privacy.

And I’m still figuring out the how for making it happen.

Happy New Year!

Thanks for reading, and stay curious!

—

Want to learn about future Freshly Squeezed games I am creating? Sign up for the GBGames Curiosities newsletter, and download the full color Player’s Guides to my existing and future games for free!