Each week, I’ll go through an exercise from Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games, Third Edition . Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

. Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

You can see the #GDWW introduction for a list of previous exercises.

This week’s exercise: describe a game as if your audience is someone who hasn’t played anything like it before, then do the same with a completely different game. Compare the descriptions.

Chapter 2 is all about the structure of games, and this exercise is meant to get you thinking about what makes a game a game.

Rune Factory: A Fantasy Harvest Moon

I’m playing Rune Factory: A Fantasy Harvest Moon these days for the Nintendo DS, and since it is so fresh in my mind, I’ll describe it first. It’s a complex game, so brace yourself.

You play the role of a young man who can’t remember who he is or where he comes from, and after stumbling across a woman’s house, she puts you to work tending the farm in return for letting you stay on the land. After fighting a monster off, there’s a hint that perhaps you were a soldier, but for now, you’ll plow the land, plant and water seeds, and clear out weeds and rocks to make room for it all.

Time

Time matters. Each day begins at 6AM, and every 10 real life seconds you are playing, 10 minutes passes in the game. You can’t stay up 24 hours or you’ll collapse, so at some point you need to go to bed. There is a calendar system that is a bit unique: each week is five workdays and one holiday long, each season is five weeks long. The seasons dictate what crops can be grown on the farm. For instance, strawberries are a spring crop, and so they can only be grown during the spring season.

Time only passes when outside or in a cave. If you are inside a building, such as your house or a shop, time stands still, which means you can explore the indoors to your heart’s content. It makes exploring the library very unrealistic. B-)

Your Home

On your farm, you have a house, which is where you sleep and save your game. I’ll describe more about the house later.

Near your house is the shipping bin, which is where you can place harvested crops, fish, or any number of items in order to sell them. On non-holidays, you can expect Rosetta, one of the people from town, to pick up everything, and you’ll get paid the next day.

Near the shipping bin is your well, which allows you to refill your watering can. You can also fill your watering can at the nearby stream, which also allows you to fish if you have a fishing pole.

At the southwestern part of your land, there is a woodshed, which is where you store any chopped wood. You can collect wood to build fences on your fields, or you can save it to expand your house or build monster huts. The monster huts will be built to the east of your house in an area north of your field.

Your field is a large area of land that you’ll use to grow crops. Weeds and branches will appear in untilled areas, and there are large tree stumps and boulders. Some large rocks can be moved, but you’ll need upgraded tools to get rid of the rest to clear the way to maximize the size of your farm.

Farming and Fishing

The land is separated into tiles. You’ll use a hoe to till a tile in your field. It’s suggested you till a 3×3 area, then stand in the middle to plant seeds in all 9 tiles at once. Then, using your watering can, you can water each tile.

Each day you need to water your fields where you planted the seeds until they are mature crops you can harvest. If it is raining, you don’t need to water them. If your plants don’t get water, they stop growing.

It can take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks to mature depending on the type of seed. After they are fully grown, the crops can be picked and placed in your pack, or you can carry them over to the shipping bin.

Seeds can only be planted on your farm during certain seasons. They won’t grow if planted in the wrong season, and you won’t be able to harvest your crops if you enter a new season in the middle of growing the previous season’s plants.

There are caves in the world around your farm, and each one has a different permanent climate. That is, even if it is winter, you can grow summer crops in a cave with a summer climate. The trick, of course, is that you need to water those crops, which takes time.

When you have a fishing pole, you can fish anywhere there is a body of water. The stream near your house is one example, but there is the end of the dock on the beach, or even the water near the ruins.

There is a variety of fish you can catch. Some are more valuable than others, and they come in different sizes which also impacts the amount you can sell them for. Don’t be surprised to find the odd boot mixed in with your prize-winning sardines.

Village

To the north of the farm is the village of Kardia You can find most of the people there. Everyone has their own simulated life. Some people show up in town only on holidays. Stores are open only during certain hours, and people will arrive or leave areas depending on where they work or who they might be talking to.

The village has three streets featuring the shops and homes of the residents. The southern street has:

- Library

- Clinic

- Parts Shop

- Pub Spring Rabbit

- Inn

- Blacksmith

The middle street has:

- Hot Springs

- Neumann’s Farm

- Camus’ Farm

- Kardia Chapel

The northern street has:

- Mayor Godwin’s Manor

- Jasper’s Manor

To the east of the village is the beach, which features the Spearfish Shack, a dock to fish off of, and a giant shell which can be used to transfer screenshots and items to another player’s game using the Nintendo DS WiFi capability.

Each of the buildings has their own hours, which means if you try to go shopping too early or too late, you’ll be out of luck.

To the north of the village is the Town Square, which is where festivals are held.

In a house to the south of your farm is where the young woman who found you lives.

Relationships

There are 28 people who you can talk to, trade with, and give items to. 10 of them are potential love interests and brides for your character.

There is a Friendliness menu in the game which allows you to see the status of your relationships. You can see how your neighbors like you, as well as how your wooing of potential brides is going.

You can increase the friendliness levels by talking to people and giving them gifts. People have preferences, so giving them gifts they don’t care about has a similar effect as in real life.

Once your love interest cares enough, and if you’ve upgraded your house and bought the right furniture, you’re ready to settle down. In order to propose to her, you have to meet some criteria. Each woman has a different set of criteria you must meet, such as how many monsters you have on your farm or giving a specific gift.

When married, your wife will provide you food each morning to start your day, which you can treat as a snack to replenish your health and stamina after a hard day’s work, or you can sell it.

If you are married long enough, you’ll have a child. As far as I know, the child has no in-game purpose other than to mark the amount of time you’ve spent married.

Health and Stamina

You have two resources: health and rune points. Rune points, or RP, act as your stamina.

Every action you take uses up RP, and when you run out, your health starts to deteriorate.

If you run out of HP in your field, you’ll collapse and wake up in bed the next day, losing a good part of your morning.

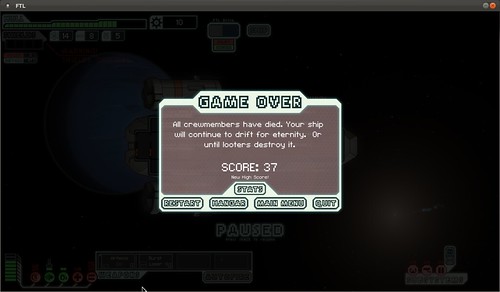

If, however, you run out of HP in a cave, the game is over.

You can restore RP and HP by sleeping for the night, by relaxing in a hot spring bath in town, or eating food. RP can be replenished by picking up runes that appear after a crop is harvested, and HP can be restored with potions or medicine.

Tools and Items

Early on, you’ll receive a hoe, a watering can, and some seeds from Mist, the young woman who allowed you to stay on her farm. By talking to people and meeting certain criteria, you can gain access to other tools, such as the ax, fishing rod, and the sickle. Each tool allows you to perform a specific task. An ax lets you cut down the branches you find on your field, which converts to wood in your woodshed, while the Friendship Glove allows you to befriend monsters you find in caves.

There is a wide range of items in the game. Some aren’t very useful, such as the stones and weeds you find in your field. Crops, herbs, fish, and eggs are examples of basic items, and if you have the right machinery or tools, you can turn them into more advanced items. For example, if you have a cookbook and a kitchen, you can turn a fish into sushi, which is more valuable and can be sold or eaten for greater benefit.

You can give items to people, although most of the time you’ll sell items for profit. You can sell items by putting them in your shipping bin on your farm or by talking to shop owners in the village.

Caves

You won’t be allowed to enter the caves until you’ve gotten a pass from the mayor, who requires you to have tilled a number of tiles on your field first.

The caves have monsters and monster generators. You’ll be able to fight them with your tools such as the hoe or ax, but you’ll probably want weapons such as swords and spears. You can also defend yourself with shields.

Fighting happens in real time. Monsters will attack you, and you can either attack back or use the Friendship Glove to try to pet them until they like you. Befriended monsters teleport to your farm if you have a hut for them to live in, and depending on the type of monster, they can work your fields, allow you to harvest items from them, or help you fight in the caves.

You’ll learn magic to teleport yourself to safety, to heal yourself, and to attack monsters. Your monsters may use magic to fight for you as well. Magic costs rune points, even if your monsters are the ones casting the spells.

Caves also have fields, and since their climate is so stable, you can plant crops you normally couldn’t at any time of the year.

You can also use a hammer against certain rocks to collect ore, which allows you to upgrade your tools and weapons.

Enough!

There are a lot more details to explain, but I think this post is getting long enough. Let’s move on, and to a smaller and quicker to describe game, please.

Iota

Iota by Gamewright, “the great big game in the teeny-weeny tin,” is a card game for 2 to 4 players. The objective of the game is to score the most points by adding cards in lines connected to a grid.

A line is defined as 2, 3, or 4 cards in a straight row or column. There are specific rules for how such cards can be placed in lines.

There are 66 square cards. 64 cards have three properties:

Each of these cards are unique. Two cards are wild and can substitute for any other card.

Setup

Each player is dealt four cards which can be looked at but should be kept a secret from other players. The other cards are stacked face-down to create a draw pile.

One card from the draw pile is placed face up in the center to act as the start of the grid.

Play

Each player takes turns and can either:

- add cards in a single line, then record your score

- pass

When passing, a player may discard any number of cards to the bottom of the draw pile.

At the end of your turn, you replenish your hand back to four cards.

Game Over

The game ends when the draw pile is empty and a player has played his or her last card, which gives double points for that turn.

The player with the highest score wins.

Adding Cards and Scoring

When adding cards to a line, there are certain rules to follow:

- Cards must be added in a straight line. You can’t place cards anywhere you choose, and you can’t make right angles.

- Added cards must connect to the grid.

- In each line, all cards must either be the same or different in each property. You can’t have a 3-card line with two circles and a triangle because the shapes must be all different or all the same, for example, but you can have a 3-card line with three circles so long as the colors and/or numbers are different.

- Creating a 4-card line forms a lot, which doubles your score for the turn.

- Lines can only be four cards long.

After you place your cards, you add up the numbers on the face of all of the cards in the lines you either created or extended, counting cards twice if they are part of two lines.

Then double the points earned for each lot created.

If you used all four of your cards, double your points again.

Wild Cards

The wild cards can be used in place of any other card and are worth 0 points.

Before your turn, you can replace a played wild card with a card from your hand that matches. That is, if the wild card is part of a line of three green circles and is acting as a green circle with a value of 4, you would need a green circle with a value of 4 to replace it.

You can then play it on any turn.

Wild cards that are part of two lines must represent the same value on both lines.

Comparing Rune Factory and Iota

One is an involved story-based, single-player, farming simulation and role-playing game. The other is a family-friendly card game that can be played in about half an hour.

There are clearly a lot of differences, but what similarities are there?

While it wasn’t called out above, Rune Factory does have a setup. The player is initially told that his or her character is a young man with amnesia. He is given his first tools and an explanation of how to work the field. Combat ensues immediately to introduce the concept of monsters. Afterwards, the real game starts.

They both have rules. Iota says how cards can be placed, how scores can be tallied, and what can’t be done.

In Rune Factory, the rules are more complex and are enforced by the programming of the game. How time passes, and how various events occur based on the time, are just some of the interlocking rules.

They each have dynamics that occur as a result of playing. If you can’t place more than four cards in a line in Iota, and if you can’t place certain cards together in a line, then sometimes gaps will occur in the grid that cannot be filled. Sometimes a player will place a card on a line that prevents another player from placing his or hers.

In Rune Factory, seeds get planted in a 3×3 grid. If you till a 3×3 grid, all will get seeds, but if you till only part of it, either due to weeds or rocks being in the way or some other reason, then you are wasting some of the potential return on the cost of seeds. If radish seeds cost 200 gold, and you can sell each harvested radish for 60 gold, then you need to sell at least four radishes to make back your investment. If you can’t, you lose money, which prevents you from purchasing other supplies.

Each has a designed look and feel to it. Iota is colorful, and the cards are of a certain quality. The cards are all you need to play, which allows you to focus on them as the main elements. Rune Factory has a lot of music, sound effects, story, illustrated graphics and animations, and more to immerse the player in the game.

Iota has a very clear ending with a victor, but what about Rune Factory? Can you win it? While Rune Factory lets you play forever, the storyline can be completed.

Exercise Complete

I am sure I can compare them in many other ways, and chapter 2 does go into the structure of games for quite a bit, but we’ll consider this exercise finished. I already found enough accidental spoilers for Rune Factory during my research, and this post is way too long now.

If you participated in exercise 2.1 on your own, please comment below to let me know, and if you wrote your own blog post or discuss it online, make sure to use the hashtag #GDWW.

Next week, we’ll compare how players start games of two seemingly different games.

. Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.