There are less than three weeks left before the Ludum Dare October Challenge ends, and I’m worried.

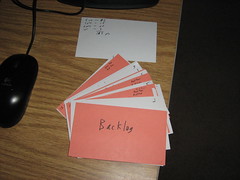

I’ve been doing weekly iterations on the assumption that I would accomplish about 20 points worth of work each iteration. After the first week, I only did 7 points of work. Not only that, but I added a few points of unforeseen work. Ok, no need to panic yet. I lost some time that first week. I can see how the next week goes. Maybe I’ll do things faster than expected.

Now that Iteration 2 is coming to a close, it looks like the first one: less than half of the work was accomplished, and extra work was found.

Ok, time to panic!

Wait, don’t panic! Part of the benefit of managing the project in an Agile way is to gain some insight into the health of the project. I’m not happy about how slow I’m going, but I am pleased that I can tell that I am going slow so early in the project. Let’s figure out why progress is slower than I’d like it to be.

In three days, I made Stop That Hero! for the Ludum Dare Jam. In two weeks, I’m barely able to draw arbitrary sprites and process input.

Why the difference?

With the Jam version of the game, I hacked it together during the time I didn’t spend eating or sleeping. My current work schedule is less intense. I spend between 4-5 hours a day on game development. Why not more?

Since I work for myself, I have no fixed hours given to me by someone else. In an attempt to give my days some semblance of structure, I’ve decided that certain hours of the day are dedicated to exercise, game development, writing, reading, and organization. I don’t have enough hours in a day to do more game development without taking time from other aspects that I deemed important. Maybe it’s too lax for a newly full-time indie game developer, but I don’t need to force myself into crunch time yet. Besides, any time outside of the scheduled time is mine to do with as I please. If it means that I occasionally have days where I work more hours, all the better. All that said, I don’t believe my work schedule is the culprit here.

As I mentioned in the post on development challenges and concerns, I’m using Test-Driven Development on this new version of the game to ensure that bug fixes and game updates are as easy as possible. If a paying customer finds a bug or if I release a new feature, I want to make sure that new code works and that old code doesn’t break.

Unfortunately, I’m paying up front for it. I’m reasonably confident that the code I’ve written works correctly. I just wish I had more working features!

What I am finding, however, is that the code is easy to use in small pieces. There’s more cohesion and less coupling. Even without explicitly trying, my code is organizing itself in a way that would let me script it more easily. It’s more data-driven, in other words.

But is TDD slowing me down? I have a deadline to sell a game by October 31st. If I can’t get a playable demo of the game completed by next week, this project is in danger of not shipping on time.

On the other hand, October 31st isn’t a hard date for my business. It’s a good target date for a fun challenge and some motivation, but I don’t have sales projections and quarterly revenues depending on it. If I take a few weeks longer to make the game good versus shoveling something out the door, I think I’ll be better for it. As an indie, I have that freedom.

So what’s the solution to my project planning?

The latest issue of Game Developer has a post-mortem about Final Fantasy XIII, and one of the things that went wrong is the development of a “universal engine”. Basically, since Square Enix wanted to create an engine that worked across all the new console hardware for all games in development, they spent a lot of time trying to make sure they accommodated every team’s needs. It wasn’t until they decided to give priority to Final Fantasy XIII over the other games in development that they were able to make good progress.

Similarly, I need to be extra wary of overengineering. With TDD and Agile, I should be implementing only what I need when I need it. You Ain’t Gonna Need It (YAGNI) is the principle I need to follow more closely. I think a big reason for my slowdown is that the things I have coded are a bit more general purpose than I need them to be right now. It will be great to reuse a lot of these features and pieces of code in different games, but it’s not helping THIS game get finished faster.

For instance, I created a basic data-driven menu system as opposed to the relatively hard-coded system I had before with code strewn about here and there in my game. I based the design off of what I read in Game Programming Gems 5. It’s easy to create menus and their buttons, and it can be extended later, and it’s unit tested to boot!

But couldn’t this game have been served by menus that aren’t general purpose? Maybe it wouldn’t be as nice, but it would have been workable and I could have spent more time on the game entities and their interactions. I clearly didn’t learn the lesson from my last post-mortem:

As in previous Ludum Dare compos, I’ve found my biggest problem is deciding where to spend my time and for how long.

I think I should continue to use TDD. It’s helping me design almost naturally-scriptable code, and there are many other benefits. What I need to focus on is finishing the game with the smallest amount of basic features implemented as opposed to spending an inordinate amount of time on any one feature. Otherwise, I’m just creating a game engine for unknown future projects and their unknown requirements.