Each week, I’ll go through an exercise from Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games, Third Edition. Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

You can see the #GDWW introduction for a list of previous exercises.

This week, I’ll quickly describe the objective of five games.

Last week I wrote that we consider Go Fish and Quake 3 to be games despite their differences, specifically highlighting the fact that they are both designed for and played by players.

Continuing the comparison, both have objectives. The goal of Go Fish is to collect the most piles of cards, while the goal of Quake 3 is to fight your way through multiple tiers and defeat the AI-controlled bots.

As Fullerton states: “the objective is a key element without which the experience loses much of its structure, and our desire to work toward the objective is a measure of our involvement in the game.”

I like that description. I can think of times I was bored with a game I was playing, and at some point I didn’t care about finishing it. I can also think of my first time playing Minecraft, and hours passed without me realizing it as I built a large castle, complete with a minecart to take me up and down the mine for raw materials.

Objectives

Ok, let’s look at some games and try to identify their objectives.

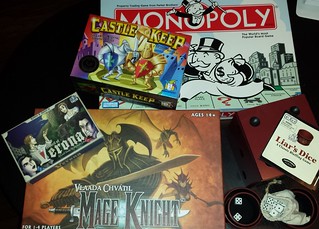

Mage Knight

Vlaada Chvatil’s Mage Knight is a very complex board game.

Very complex. There are a lot of moving parts in this game, and a lot of rules related to moving, attacking, hiring units, taking damage, exploring new tiles, revealing enemies and artifacts, leveling up your hero, raising and dropping your reputation, and more.

But ultimately, whether you are trying to find the city in the first scenario or liberating mines in a competitive scenario, the objective is to gain the most Fame, which represents how well you are doing and can be seen as victory points.

Monopoly

I used to be obsessed with Monopoly. I was never a fan of all of the [insert licensed brand here]-opoly derivatives, partly because they aren’t just themes but actually changed the rules.

A number of game designers might argue that Monopoly is broken game, and I know of a number of players who complain that it takes too long to play, but a lot of people get surprised when you tell them that there is a difference between what the rules actually say and the version of the game they probably played.

For instance, you don’t put money in the center whenever you pay the bank, and you don’t get to collect anything for landing on Free Parking.

Also, housing shortages are a tactic. The game has 32 houses and 12 hotels. If you want to buy a house, but all 32 are already being used by other players, too bad. You don’t get to use a scrap piece of paper to act as a placeholder. You just don’t get to buy a house.

It’s why I never buy hotels, because the fewer houses available for everyone else, the better off I am. It’s also why getting expensive properties might not be the best strategy because someone with cheaper properties can buy houses much more quickly than you can, leaving you with fewer or no houses, ruining your higher rent advantage.

The objective of Monopoly is to bankrupt your opponents, and without arbitrarily adding house rules to pump extra resources into the economy of the game, the negative feedback cycle is a lot quicker.

Council of Verona

Michael Eskue’s card game Council of Verona has a Romeo and Juliet theme.

It’s a quick game, and it’s easy to learn. People I’ve introduced it to picked it up within a game or two, and they seemed to enjoy it enough to keep playing.

In the game, you have the Council and Exile, and you take turns playing your cards, each of which has a character such as Prince Escalus or Lady Montague. Some characters allow you to play an action, such as moving a card from the Council to Exile or vice versa, and other characters have Agendas.

The cards with Agendas are the key. You bid your Influence tokens in the designated areas on these cards, and if the Agenda is met, the Influence tokens are counted and scored. Agenda examples are Romeo’s”Romeo and Juliet are together” or Lord Montague’s “More Montagues than Capulets on the Council.”

The objective of Council of Verona is to score the most Influence points.

Castle Keep

Castle Keep by Gamewright is another enjoyable and quick game.

It’s a turn-based game in which players draw and place tiles made up of castle keeps, towers, and walls. There are three colors possible for each type of tile, and towers and walls also come in three different shapes. You can place tiles next to each other if they match either in shape or color.

Instead of building your castle on your turn, you can attack one of an opponent’s walls. Any adjacent tiles of the same color as that wall are also destroyed, so there’s a danger to consistent interior design.

Castle Keep offers two objectives: to be the first to build a 3×3 castle or to destroy an opponent’s castle.

Liar’s Dice

Liar’s Dice is a dice game that should be familiar to anyone who has seen Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest.

It’s a bluffing game. Each player starts with a set number of dice. All players roll their dice and peek at them in secret, and then each in turn makes a bid about how many dice are showing a specific number. For instance, you might bid that four dice show the number 3, and the next player might bid five dice showing the number 2.

After a bid is made, the next player can challenge the bidder, and everyone shows their dice. If the actual number of dice showing the number specified in the bid is equal to or greater than the bid, then the challenger loses one die from his or her collection.

If, however, the bid is not made, then the bidder loses one die from his or her collection.

The objective of Liar’s Dice is to be the last player in the game with any dice.

Exercise Complete

Clearly the objective has a huge impact on how a game is played and also how players are engaged. If you are low on dice in Liar’s Dice, you might be more conservative about bidding than if you had a full collection. If your opponent is closer to building a castle than you are in Castle Keep, you might be more interested in finding ways to knock down his or her walls than on trying to catch up.

If you take away the objectives of these games, there’s no point in playing anymore.

If you participated in exercise 2.3 on your own, please comment below to let me know, and if you wrote your own blog post or discuss it online, make sure to use the hashtag #GDWW.

Next week, we’ll focus on the rules of a game.

One reply on “Game Design Workshop Wednesday Exercise 2.3: Objectives #GDWW”

[…] Exercise 2.3: I describe the objectives of give games […]