A couple of years ago, I purchased a number of books by Ian Bogost, the game designer, author, and professor who also created the parody game Cow Clicker and one of my favorite things on the Internet: buns.life, which lets you put words between buns.

I can’t remember why I decided to buy multiple books by Bogost at the same time. I imagine it was because Racing the Beam was on my wishlist for a very long time, and when I finally decided to get it, I thought, “Yeah, I could stand to read more books about games.”

I finally got around to reading these books recently. In fact, I read each book within a week before moving on to the next, so I felt I got quite immersed in Bogost’s world in a little over a month. I could trace lines of his thoughts as they evolved over time and also recognized the same references he makes across multiple works.

Here are some brief thoughts on each.

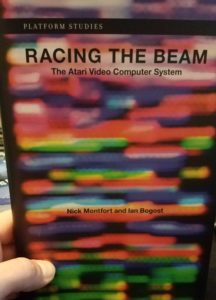

Racing the Beam

Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System, co-written with Nick Montfort and published in 2009, was a joy to read as someone whose first experience with video games was my family’s own Atari 2600 that I still have in my possession.

The book covers both the technical details of the Atari VCS, what I always knew as the Atari 2600, as well as analyzing how it impacted what kind of culture was being created by the developers who worked on the games for it.

I learned a lot about the history of Atari and the people involved in it, the reason why games worked the way they did for this platform, and how the system was flexible enough that it allowed for such a wide variety of games to be made for it, way beyond what could have been expected when it was designed.

There were times when I wished to dive even more into the technical details of how the system worked, but what was provided was probably deep enough for the target audience. Besides, I am sure there are actual manuals and guides for that kind of depth.

But I also enjoyed reading about the Atari 2600’s place in terms of the time period, the market, the politics, scandals, and more. I liked the insight that came from what were seen as poor quality arcade ports in terms of what it takes to make something successful as an adaptation. I liked learning about the names of the people behind some of my favorite games for that system, as well as learning more about the constraints they worked their magic within.

Despite diving into the details of a piece of hardware, I found this book to be one of the more accessible ones to this non-academic.

It’s also part of a series at MIT called Platform Studies, and I know I have copies of a few of those books thanks to Humble Book Bundles, so I look forward to diving into them soon.

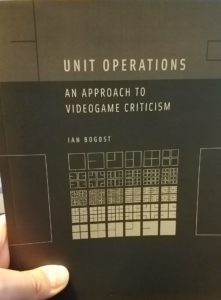

Unit Operations

While I found Racing the Beam to be accessible, I found Unit Operations to be a challenging read. I felt smarter within a few page partly because I had to look up a few words because the rest of the sentence or paragraph that they were encountered didn’t seem to give me enough clues to their meaning.

This was a book written for an academic audience. I had to work for it, and I’m glad I did.

Unit Operations has a copyright date of 2006, and if I managed to successfully understand it, it was Bogost’s attempt to create a grand unifying theory of criticism that would work for not only games in particular and computation in general but also cover typically criticism-comfortable ground such as literature and poetry and film.

This book covered everything from philosophy to art to computer science to psychology to film and of course games.

Much like with Racing the Beam, I enjoyed the placing of context of different pieces of work. I happened to listened to a course on Western philosophy a few years ago, and so I was able to get references to major thinkers and writers.

As for a unit operation, well, my understanding, which might be wrong and not nuanced enough, is that a unit operation is a “thing that has meaning.” Specifically, a thing that can be combined with other things and understood with its relationship with those things in that specific combination.

That “thing” can be a cog in a wheel, or the wheel itself, or the concept of machinery in general. Bogost talks at one point about object-oriented software You can write a piece of code as a component of a larger system. Maybe that system is a component of an even larger system. But each component can be understood both in isolation and as part of the system it operates within. And the components work together differently if they were combined in a different way. The components in a particular configuration allow for certain operations and meaning-making. I wasn’t sure if I followed his understanding of “object technology”, but the general idea of procedural meaning seemed to make sense.

He talked about the Baudelaire poem “A une passante” which “expresses a unit operation for contending with the chance encounter.” It’s love poetry about the fact that the woman walking away in the busy and modern Parisian atmosphere will never be someone the author will meet. Walter Benjamin named this idea “a figure that fascinates” as it isn’t about the woman so much as a lost chance at connection.

Baudelaire was trying to figure out how to make sense of this new modern city life. This chance encounter idea was kind of new. The loneliness despite being among so many people was new.

Decades later when Charles Bukowski wrote “A woman on the street” it similarly was about that figure that fascinates, that lost chance to connect. Bogost argues that this concept went from being a novel experience to a meme-like cultural understanding. In a way, everyone understands this concept now, as everyone knows what living in modern society is like, and so instead of needing to describe it in detail, you can use shorthand.

It became a unit operation, a way to help us understand the meaning behind it all.

And then Bogost explored how it applies to The Sims expansion Hot Date, exploring the unit operation in the simulation that the game provides of modern urban living.

And the book was filled with similar analysis across multiple types of media.

I think one major takeaway I got from Unit Operations was the idea of simulations, and games in particular, being necessarily subjective. Bogost’s definition of a simulation focuses on the gap between what the simulation represents and what the user brings to understand it.

But I think that in light of complaints by some gamers that politics should stay out of games, I think it is interesting that there is this idea that all games are necessarily political because the game creators had to decide what to simulate and what not, what to put in and what to ignore, what to model and what not to.

I think I am glad that I read this book now as opposed to when it was released, because I don’t think I would have understood nearly as much. I expect that if I reread this book in five or 10 years that I’ll pick up some nuances or learn that I completely misinterpreted an aspect of it that I would grok much better then.

But I really appreciated how this book brought together so many seemingly different subjects. I find I can be fascinated by anything, and this book put a lot of anythings within easy reach and allowed me to see them all next to each other in a very satisfyingly holistic way. I remember finishing it and thinking, “I wonder how often unit operations will come up in other works” but I did not see them mentioned in his other books, and I wondered if it meant that the concept did not catch on.

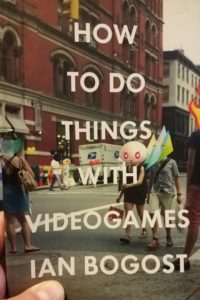

How to Do Things with Video Games

In 2011, Bogost published How to Do Things with Video Games and explored the relevance of games as a medium by analyzing what spectrum of possible uses they can be employed.

I mean, you can play games, sure, but more than that, games can be used to make art, or to train, or to persuade, or sell, or exercise, or anything in between.

Each chapter explores one use that games have already demonstrated they are capable of. Rod Humble’s The Marriage usually comes up when talking about games as art, but there was a chapter about using games for politicking that touched on Bogost’s own work in creating a game for a U.S. Presidential election. There was one chapter on promotion that focused a bit on Burger King’s series of Xbox games, comparing it to similar efforts at promotion in the 80s and demonstrating that games have a long history of allowing people to do a variety of things with them.

I think one thing that struck me was that Bogost argues that games aren’t just for the stereotypical gamers anymore. The idea of the gamer will be as silly as the idea of the movie watcher. You just have people, and people might play games. A few years after this book came out, there was an ugly and sometimes violent backlash against women who wrote essentially the same thing. I don’t recall hearing Bogost getting the same vitriol thrown at him, but I could be wrong.

How to Talk About Video Games

The next book I read was 2015’s How to Talk About Video Games, which addresses the idea that games, while different from other media, shouldn’t be treated as either special or less than.

Specifically, Bogost was unhappy with the idea of “games writing” or “games criticism” because it risks isolating games from the rest of the world. People can look down on games, and they can get away with it because society as a whole looks down on games.

In the intro, he says “This is a book full of … attempts to take games so seriously as to risk the descent into self-parody. Or even, to embrace that descent, since caricature is another means to truth.”

And it is here that I have to say, at the risk of offending Bogost, that multiple times in the previous books I thought to myself, “Ok, are we actually being serious here, or is this an elaborate joke?”

Around the time I was reading Unit Operations, I saw Bogost tweet “Sbarro Studies, Year One.” Clearly, THAT was a joke, but there were times where I fully expected it to be mentioned in the wide array of topics and subjects that the book addressed.

How to Talk About Video Games is a series of chapters that offer some kind of analysis or criticism about games or game publishers or the culture in which a particular type of game is popular.

My favorite chapter is the one about Ms. Pac-Man titled “Can a Gobbler Have It All?” It covers the pre-history of the game, going back to insights about the Atari 2600 again, the way arcade machine enhancement kits functioned both technically and economically, and finally argues that the creation of Ms. Pac-Man the game and the character has a deep connection to the roles women have in society.

Bogost admits that making parallels to the creation of Eve from Adam and to women who want to excel at a career and a family life seems absurd, but then proceeds to make a very compelling case by talking about how the game character was marketed, the story within the game, the origins of “Ms.” both as an abbreviation and as part of the title of the game, and more.

She is, after all, the first female lead in a videogame. Everything Pac-Man can do, she can do – and better. Her job is less predictable and more exciting, making it more challenging and rewarding. And yet Ms. Pac-Man is a traditionalist, a family woman willing to make a home with the right man – one whom she chases as much as he chases her – and a mother, able and willing to care for her Pac-progeny.

Bogost argues that the culture around games has fooled itself into thinking it is bigger than it really is. I am reminded of an article I once read in The Escapist when it was new and still trying to recreate a print magazine experience awkwardly on a web page, in which someone was surprised that there were gamers who didn’t read enthusiast magazines and websites about games. That people showed up at GameStop or Babbage’s and just didn’t know what the heck they were about to buy.

But there are a lot of people who don’t know inside baseball about the game industry, and it is easy to think, with an industry that has eclipsed Hollywood’s revenues, with more people playing games than ever, that it’s them who are weird.

I think the conclusion for Bogost follows from How to Do Things with Videogames, that rather than double-down on insisting that games are the most important medium of expression, and therefore marking them as different and special from the world, we can just live with games. There is no need to insist on the one true game that only gamers play. Games are for everyone, and there can be some games that appeal to only certain audiences, and games don’t need to be a sole focus, and that’s OK.

Play Anything

Play Anything, published in 2016, is one of the deepest dives into the concept of play that I’ve ever read. Which, as I already admitted I am not an academic, might not mean much, but still.

It also surprised me because it was about how to enjoy life, and as I turn 40 and keep an existential crisis at bay each day, this was an important message for me to receive.

I loved the beginning in which he talks about the modern popular use of irony as a way for people to avoid deciding whether or not they “mean to mean” something, as a way to avoid engaging with something to protect against disappointment or disaster.

Are you wearing that t-shirt of that brand as an expression of how much you like that brand or as a parody of people who would do that? With irony, you don’t have to choose. You can be neither of them. You can avoid what you are afraid of, which might be that brand betraying you by turning out to be a terrible faceless corporation after all, or that rejecting the brand isn’t very interesting.

So there’s an indecisiveness to engaging with things that comes out of fear, and our world today has a lot of things. Bogost argues that rather than hoping for something to be more than or less than it is, we can take it and accept it for what it is.

Perhaps the problem that afflicts us is not having too many possessions (or too few), or too many choices (or too few), but in failing to know how to treat anything with enough respect that its existence feels like an opportunity rather than a burden. And not an opportunity because we get something back from it or because we can put it to maximally optimized use, but because we can train ourselves to approach it for exactly what it is, rather than wishing it – or we – were something different.

The theme of treating reality honestly, of accepting what is, and of entering into relationship with that very real reality instead of trying to manipulate it into something it isn’t comes up a lot.

Play for Bogost isn’t compatible with irony, in which you hold things at a safe distance, neither accepting nor praising nor rejecting them.

Bogost argues that play is an inherent property of things. Irony’s position is that things aren’t going to be sufficient, and play’s position is that, duh, of course they aren’t, and that limitation in things is interesting and potentially enjoyable if you come at it the right way. Play is about doing what you want with what is there, and fun comes from exploring the possibility space there, especially when you think you’ve seen it all.

It’s not just mindfulness, about being aware of my own thoughts about them, but an awareness of everything else that isn’t me.

It’s about seeing things, really seeing them, paying attention to them, and doing what we can with them without being disappointed that they don’t offer something they can’t.

Conclusion

I felt a sort of kinship with Bogost. Here’s a person who also seems to love to explore a wide variety of topics, seeing and finding connections between different areas of study, and expecting to find that those connections exist.

As a game developer, as someone who is trying to create meaningful experiences through entertainment, I think I have gained a much greater appreciation for what is at stake, what the work involves, and how it relates to life in general.

I recognize certain modern debates as continuations of discussions that have been happening for centuries related to other media. I’ve found that my understanding of games as a medium has been grounded a lot more.

I think it is interesting to see how some things have borne out over a decade after he wrote about them, such as how relevant games are in politics or how the concept of the gamer is still alive and well despite the fact that pretty much everyone plays games.

And I think I’ve gained an appreciation for living a life in a way that I can appreciate living. People say life is short, that you should do what you love, that you can stop and smell the roses or practice gratitude or whatever. Maybe it is also due to the pandemic revealing a lot of the absurdities we as a society have tolerated needlessly and sometimes fatally, but I’ve found myself more and more seeing situations for what they are. While I can’t say I’ve found a way or motivation to play in a dysfunctional corporate environment or play in the misinformation surrounding COVID-19, I’ve given myself permission to have some agency in whether I participate in someone else’s constraints or my own.

Life is more enjoyable when it is honest and authentic, when you can explore the possibilities it provides, and when it is well played.