Each week, I’ll go through an exercise from Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games, Third Edition. Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

So far, I pretended to be a tester for the indie hit FTL and documented everything I experienced and did in the game, I critically analyzed a game that was “dead on arrival”, and last week I listed and described areas of my life that could be games. For this week’s exercise, I had some homework to do: keep a game journal.

This exercise comes from a section about becoming a better player. Fullerton argues that, much as an artist learns about drawing by learning about what makes for a good visual composition, a game designer learns about games by learning what makes for good game play.

In keeping a game journal, I’ll have a log of games I have played, as well as a deep analysis of specific experiences and how the mechanics of the game allowed for them.

One challenge I had with this experience is that I found I didn’t have anything to log each day. I don’t play games often enough, it seems, and I’m always surprised to read about indie game developers with day jobs who make time to not only play games but finish them. How are they not struggling with the choice of playing games as opposed to making them?

But I’m not completely isolated from games.

4-Point Pitch

This past weekend I went to visit my wife’s grandmother, who is a really good 4-Point Pitch player. Pitch is a trick-taking card game, and it turns out that there are many variations. I can’t seem to find the specific variation my in-laws play, so I’ll try to describe it here. The game is played with a standard 52-card deck with the 3s, 4s, 5s, and 6s removed. There are a few variations depending on how many players you have. We played with four players, which means we split into two teams of a pair of partners. My wife was on my team, and my sister-in-law played on her grandmother’s team.

The goal of a round of pitch is to win your bid. Bids aren’t based on the number of tricks, but on four criteria: High, Low, Jack, and Game. High is when you win the highest card in the trump suit. Low is for playing the lowest, which means you can still get it even if you don’t win it in a trick. Jack is winning the Jack of of the trump suit. Game is for ending the round with more points from the tricks you took, and points are assigned as follows:

- A: 4

- K: 3

- Q: 2

- J: 1

- 10: 10

No other cards count towards game.

For a given round, there are up to four points your team can earn; however, since there are six cards in a hand, with four players, it means only 24 cards are dealt, leaving 12 cards no one knows aren’t in play. While there will always be a highest, lowest, and most points taken in a trick, there might not always be a jack in the trump suit dealt. Bidding four is a rare enough occurrence in a six-player version of the game in which all of the cards are dealt, but it almost never happens in the four-player variant.

Typically, a safe bid is made when your hand has enough cards in one suit that guarantee you’ll win. For instance, having the Ace and 2 of hearts, you know you’ll have High and Low, so you might bid two.

If you have the Jack and 10 of spades, however, you might not want to bid. Why? If you throw the Jack out, someone else might have the Ace, King, or Queen of spades and take the trick, and if it isn’t your partner, you’ve just lost a point, and possibly two or three if the other team played the highest and lowest spades. If you play the 10, and your partner can’t win the trick, you’ve just given a huge advantage to your opponents for winning Game this round. It’s probably safer to pass on bidding with these cards.

Most of my wife’s family seems to play fairly conservatively. My wife’s grandmother likes playing with me, however, as I make riskier bids to make the game interesting. I’m told that when her husband was alive that he would make four bids consistently with the most surprising hands.

As I said, there are 12 cards not dealt in a 4-player game. You might want to think about the odds that anyone else has the cards to beat yours, much as I did in one round.

I had three hearts: a Queen, a 9, and an 8. Normally, this is not a strong hand. There are potentially two higher cards than my Queen, and there are potentially two lower cards than my 8. What’s more, there are four cards that can beat my 9 that I don’t have, and if my 8 isn’t Low, they can beat that card, too.

And yet, I bid two. And since no one bid three, I won the bid, which means I get to play the first card, which indicates which suit is trump for this hand.

I played my Queen, and my partner played her Ace, which means we won the trick and have High. Later, I played my 9 to win a trick that was going in favor of our opponents in an off-suit, which allowed me to play my 8. Once again, my partner had the better card in a 2, and we made our bid. In fact, we also won Game as we took enough tricks to have more than enough points.

It was at the end of the round in which it was noticed that I bid two on such a terrible collection of cards. My wife pointed out that we were lucky she had the Ace and 2, although I was quick to point out that if she didn’t have those cards, our opponents did not have anything to beat the cards in my hand so we would have won anyway.

And this is how it goes for me when I play Pitch with my in-laws. I make risky bids, and while sometimes they go badly, often I’m able to pull it off, and yet I still get scolded for it. B-)

I get scolded because of those incredibly rare (My wife: “Hah!”) times when I don’t make my bid. In this same game, I bid three on a Jack, 10, and 7. As I mentioned above, the Jack is at risk here because someone else might have a higher card and win the trick I play it in. I played the 7 first, and luckily, it was Low. However, the rest of the round went badly for our team as it turned out that our opponents had better trump cards. I knew it was a risk, yet I bid anyway because I thought there was a chance I could pull it off since the big unknown was if anyone else had the cards to beat my hand. Sometimes there are no Aces, but to have no Aces, Kings, and Queens in play of a particular suit is a bit more unlikely.

The thing about this game that always intrigued me was that there were multiple ways to earn a point. While High and Jack can be treated similarly in that you win the hand the appropriate cards are played in, and Game requires counting points in the tricks you won in the round, Low is different. You win Low by merely having the lowest trump card in your hand. You don’t need to win the trick you play it in.

Why was it designed in this way?

In my research, I learned that I’ve been thinking about it the wrong way. You always win the hand when you play the high card, but that fact is incidental. The real way to get High is merely playing the highest value trump card, much like getting Low is done by playing the lowest value trump card. There’s symmetry there that I didn’t recognize before.

I’ve seen variations of Pitch in which the way to get High and Low is to win the trick that has those cards played. I haven’t played it that way, but it seems to me that it would change how often Low would be won by the team that played it since it isn’t a guaranteed point anymore. Someone on the other team might take it if they have a higher trump card.

Instead of getting Low based on the luck of the draw, you would need skill as Low is nothing more than yet another card that happens to be in the trump suit. This change has the benefit of making the rules easier to remember for a new player, yet tilts the odds in favor of veteran players.

Baseball

My wife’s grandmother lives in a small town, with a population of 60. At its peak it had 220 residents in 1910. It has a rich history, including the fact that Bonnie and Clyde came through and robbed a few of the buildings back in the 1930s.

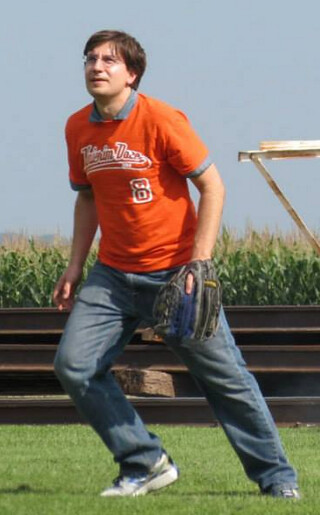

This weekend, there was an annual town reunion, and attendees were able to participate in a slow-pitch baseball game in the park between the soy beans, the corn field, and the railroad tracks. The teams were a mix of grown-ups and children, and there were way more than 9 players on the field at any given time. It was a friendly game with the goal of having fun as opposed to winning (yes, my team lost).

I don’t think I’ve played baseball since Little League, but I picked up a glove and ran out to center field, and as soon as the first ball was hit, I realized that I still remembered what to do.

Even if the ball is going out to left field, I ran in that direction to support the fielder there. If he or she dropped a fly ball, I could immediately pick it up and throw it in, which reduces the time to threaten the runners with getting tagged out. A few seconds can make a huge difference.

Depending on the skill of the batter, the fielders would move in or out. While I get why it makes sense tactically, I always felt bad about doing so. Imagine being the kid batting after the power hitter and seeing all these fielders walking towards you, knowing that they think you can’t hit the ball very well. That’s not great for their confidence.

When the ball did come to me out in center field, I had to throw it towards the infield, but to whom? 2nd base was usually a good bet, as it would prevent the batter from attempting to run there, but what if someone is running for third? And if someone is running home, you better have a good arm to get it there, and I…I do not. So my default was to throw to 2nd base, or to shortstop if the fielder came out to help relay the passes.

But as I said, it was a game for mixed ages, and the rules and winning weren’t everything. I wasn’t the only center fielder, and if a young child got to the ball first, I resisted asking for it despite the fact that I would throw it much faster. This is his or her moment of glory on the field, after all, and whether the child threw the ball or ran it allllll the way to the infield, there was the delight they had for participating that you didn’t want to take away. And the parents and grandparents in attendance got a thrill, too.

I think a favorite moment for many people there was the very small child who ran the bases in a creative way, managing to run from 1st to 2nd to home, despite the existence of a runner standing on third. I’m sure we could have enforced the rules there, but you try telling that kid he didn’t actually score a homerun off of his 8th swing which barely touch the ball.

Speaking of running, when I hit the ball, I remembered the coaching I received as a child: run all out to first base, run through first base, and turn right if you don’t plan to run to second. In baseball, you can run through 1st base and still be considered safe because…well, I never looked into it, but it’s special. If you turn left, however, it means intent to run to second base, and you can be tagged out in that case, but turning right means you are staying at 1st and just need to slow down.

It’s an interesting rule, because running through first means you get to run at full speed all the way to the base. If you had to stay on the base in order to be safe, it would mean needing to slow down somehow, which makes it easier for the fielders to get the ball to first to tag the base and force you out. It also reduces the risk of injury, as being able to run in a consistent manner seems safer than running all out, then trying to stop on a dime.

Exercise Complete

Despite not playing many games, I was able to journal a bit about the few I did play. In one game, I finally had an excuse to look into a rule that interested me for some time, and in another rules were broken in the interest of having fun.

I’ll continue the game play journal as it definitely seems like a good idea for me to practice identifying what mechanics seem to help or hinder the player’s experience.

If you participated in exercise 1.4 on your own, please comment below to let me know, and if you wrote your own blog post or discuss it online, make sure to use the hashtag #GDWW.

Next week, I’ll describe 10 compelling aspects of childhood games I remember playing.

One reply on “Game Design Workshop Wednesday Exercise 1.4: Game Journal #GDWW”

[…] Exercise 1.4: I kept a game journal […]